Reconsidering “Immersive”

I really struggle with the term “immersive,” or maybe I don’t struggle but am really critical of how it is being used, as so many people have different definitions for it. It has become a keyword, a buzzword used to sell tickets, rather than a concept explored within the rehearsals and production process. Previously, when I saw the word “immersive,” I referenced the large-scale work of Punchdrunk, with my first-ever immersive production being “The Drowned Man.” Therefore, there were a lot of high expectations linked to that word. However, because of some of the more commercial Fever-type experiences—usually a warehouse with a bit of projection and sound, lacking substance for consumers beyond taking Instagram pictures and leaving—my expectations have shifted to the other end of the spectrum. So now, I shy away from the word, almost disassociating the term entirely with my own work. But my work is interactive-led and therefore in fact, immersive.

Embracing Anti-Disciplinary Artistry

One of the most important teachings during my studies was understanding the scale of immersivity and that there are different levels and perspectives of it, as people feel things differently. So who am I to complain about Fever?

I am an anti-disciplinary artist.

I had an issue with sticking to the text and respecting stage directions while studying. I was much more excited by concepts, the audience experience, and the design; the text and narrative came after. I thought there was something wrong with me, and this was prohibited in the world of theatre until I was introduced to a range of practitioners who had similar urges. While studying for my master’s, I also realized I am interested in so many different things and how they work, so I spent time figuring out how to make that my thing—what I specialize in.

Defining Anti-Disciplinary Artistry

“Anti-disciplinary Artist” has a rolling definition. It shifts according to who I am talking to and what I am talking about, but the basics of it, as of now, are about drawing from several different fields or disciplines and allowing them to collide—the collision part is very important; it’s far from polite, very bold and ambitious. We have this saying in the rehearsal room for when a proposed idea is being critically evaluated or “ripped apart”, we say “fight for your rights!” This gives the artist space to fight for their idea and for a way it can exist. But back to the definition, these different disciplines and ways of thinking must collide to create and imagine something new—spaces and concepts that do not fit into anything already existing. This, in turn, means I spend a lot of time struggling to explain particular concepts, frameworks, and methods as they do not have any history. It’s only when someone comes to see a show or watch a rehearsal that they have that “oh!” moment.

Facilitating Collaboration: The Rehearsal Room as a Playground

Most of the time, my role involves:

- Providing tools for collaboration among the varying disciplines and artists in the room.

- Providing a space to facilitate failure and ways of resolving it. This work is so far from traditional and requires proactive resolution, quick processing of failure to try again, or ways of turning failure into something useful.

- Creating a shared language quickly and establishing vocabulary, usually based on some of our big inspirations in creating immersive work—including wrestling (more specifically WWE) and KPOP.

- Facilitating a space that removes this “polite collaboration” and empowers collaborators to be disruptive and think so outside the box that we forget the box exists, and challenge each other.

- Spending a lot of time researching how other disciplines work, ways of communicating, ways of ideating, what their focuses are, and how we can bring those methodologies into what we are doing, especially if they are successful in their industry.

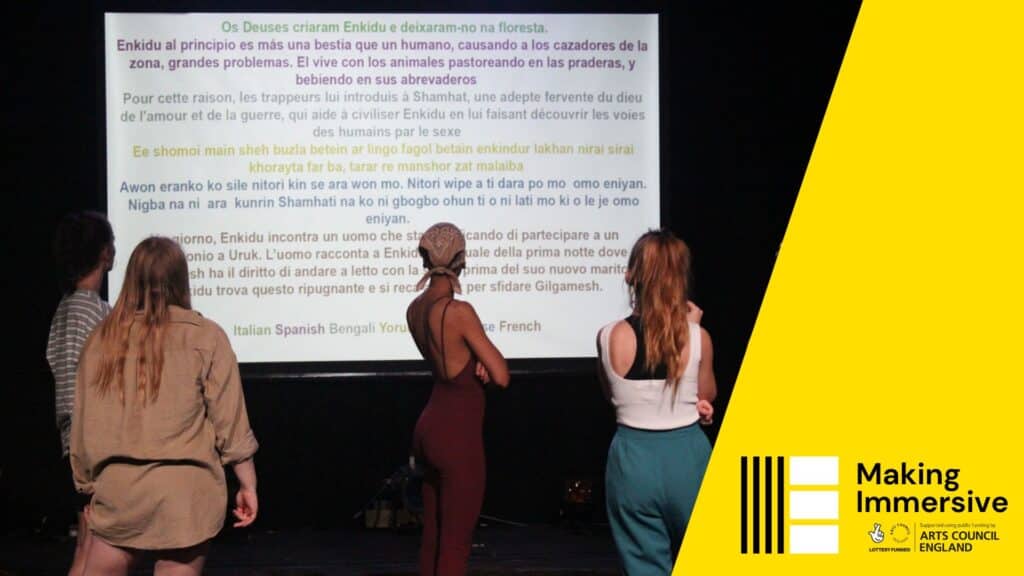

“How To Build [The City]”

One of the most complicated projects I’ve undertaken is “How To Build [The City].” It’s a devised performance based on the epic of Gilgamesh, functioning as an immersive and interactive playground where the audience follows a search for immortality. Commercially I describe it as an immersive game-show, a multidisciplinary gaming experience that focuses on how to rebuild, redesign, reclaim our city, and our relationships.

In this production:

- Group A: Six performers follow a narrative exploring themes of humanity, friendship, love, heroism, and community. Ticketed audiences contribute vocally and physically through interactive activities, shaping scenes that Group B further investigates in real-time.

- Group B: Another six performers stationed outside around the local area, collaborate with local businesses and random people in public spaces. They transform responses from Group A into tasks, games, and challenges, creating spontaneous communities and adding another layer of audience contribution.

Each scene presents unique challenges and depends largely on what audiences give us:

- Scene W: Character A engages with patrons at a local salon on processing grief, with responses projected behind a physical dance scene representing a character’s death in Gilgamesh.

- Scene X: Characters’ live locations are projected, prompting audience members inside to guide Character A to Character B, while those outside facilitate a treasure hunt-type game to lead Character B to Location C.

- Scene Y: Audience volunteers visit Location C, engage in tasks, and potentially end up on a dinner date with a character.

- Scene Z: Members of the audience engage in a game of volleyball with strangers in a local park while a character completes a 10K run, live-streamed via Instagram.

This complex web of interactions creates a kaleidoscope of responses and experiences, blurring the lines between performance and reality.

Empowering Creative Engagement

The point is we have produced this playground with many different intermingling tasks, in which we all have a shared responsibility to complete and solve. This may not necessarily be the Punchdrunk definition of immersive, but the high level of participation and audience presence means their participation is vital and crucial. As an audience member, you will be indeed immersed in action, and the fact that they are playing within reality also heightens their senses and activates sensitivity as you would from immersive theatre.

In its early iteration, it was a performance with 10 scenes, each scene taking on a different style of performance from naturalism to dance theatre and durational performance art. There was this one scene in which the performers would play a game of tag but blindfolded. I remember watching the audience’s visceral reaction, some on the edge of their seats as the performers played with different wild techniques and stunts to try and tag each other without being able to see each other. Very high tension high stakes. But it was in that moment I wondered how possible it was to involve the audience in not just this game but all games we play on stage and what that does. I have always been interested in competition and what playing competitively does to a social group, from Monopoly to Uno and Articulate; when the board hits the table, there is this elevation—it’s no longer “just a game.”

Conclusion; Fostering Collaboration from the Ground Up

The rehearsal process is similar. The first two weeks are spent exploring the themes and corresponding games and tasks; there is no, “Oh, I am an actor, so I only focus on acting…” or “I am a lighting designer, so I only focus on lighting.” In fact, we open up rehearsals to everyone interested in building with us—from lawyers to poets, bus drivers, coders/developers, and doctors—an open rehearsal where we split participants into groups. Then we give them a theme and a community partner, and they go off to do fieldwork to build these games and make connections with relevant partners, whether that’s a restaurant or local bus garage. It’s about exploring the area practically and having these creative conversations. There is a lot of testing before we return to our disciplines. I have always been interested in challenging the norms of the rehearsal room. How do we make rehearsal more transparent or more of a workshop for audiences to be a part of? I like to build in the audience participation from the foundations of the show, not just at the end in the space, which sounds obvious but is not always the case. This is a highly complex project to break down in less than 800 words, but our main foundation of immersivity is the audience as collaborators. Audiences aren’t just spectators. When building this show, or more… “this experience,” we were not interested in the audience sitting in a dark room watching a show and nodding and raising their hands when asked a yes or no question. In order for the show to work, we need audiences to participate, and the more they are willing to give, the more they buy into what we are presenting. The show is all about live response, live reaction, and improvisation, which means we facilitate discussions and empower creative engagement for all.