The placebo effect is a real and replicated clinical phenomenon in which patients are given a sugar pill containing no medication at all, yet their bodies respond as though that pill is real.

I’ve always found this mindblowing enough, but only recently heard about the follow-up finding: a meaningful placebo effect frequently happens even when the patient knows that the pill they’re about to take is nothing but sugar.

We used to think this unleashing of the mind’s incredible transformative powers relied on deception, but it turns out it’s even more interesting than that. Positive expectations and participation in a ritual might be the crucial factors in causing beneficial physiological change, even when we’re fully aware we’re playing pretend. If pretending can be so powerful, what does that mean for immersive experience practitioners – aka professional pretenders?

Immersive experiences are a sugar pill for our reality, allowing us to access internal states we might find difficult to trigger on our own, and using exactly the same mechanism as the placebo effect. Medical application aside (as much as I’d love Punchdrunk on prescription) I’m fascinated by what these experiences can do to us, how they do it, and where they might go.

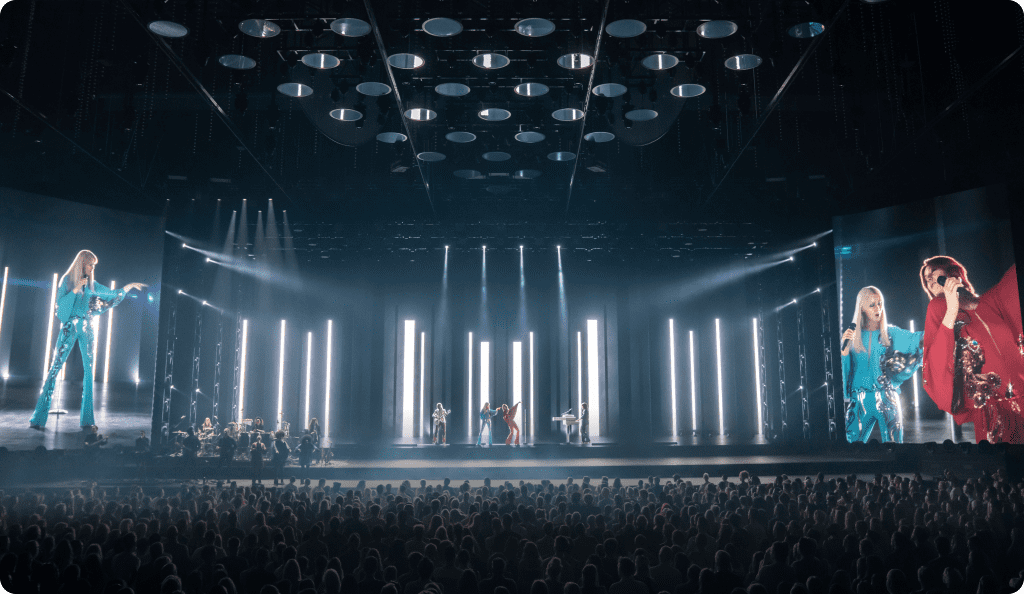

Like every other immersive enthusiast I have a long list of examples of physiological responses – getting goosebumps at AURA; butterflies of anticipation while travelling to the rave during In Pursuit of Repetitive Beats; a sudden childlike panic in the dark of Viola’s Room.

I got the tickets, I absorbed the description, I even understood how the work was made. I was well prepared but – when actually immersed in the experience – my body still decided that this imaginary scenario was really happening.

More than just a good time, I wanted to talk about the measurable transformative effects, and useful applications, of the make-believe worlds we create, so I contacted some experts to chat about it.

Katherine Templar-Lewis is the co-founder of Kinda Studios, a neuroaesthetic and neuroscience studio. Her background is human science and interdisciplinary science, but she also studied physical theatre during the rise of immersive theatre, and works frequently with big brands like Meow Wolf, alongside Goldsmiths and UCL. It’s the perfect combination of perspectives for this particular discussion.

Kinda Studios apply scientific knowledge to, among other things, the design of immersive experiences. Their work is influenced heavily by neuroaesthetics, which is essentially the way our brain processes art. “We can help guide creative choice when it comes to sound, to lighting, to spatial awareness,” explains Katherine, “to make creative choices that have a positive impact on people’s wellbeing.”

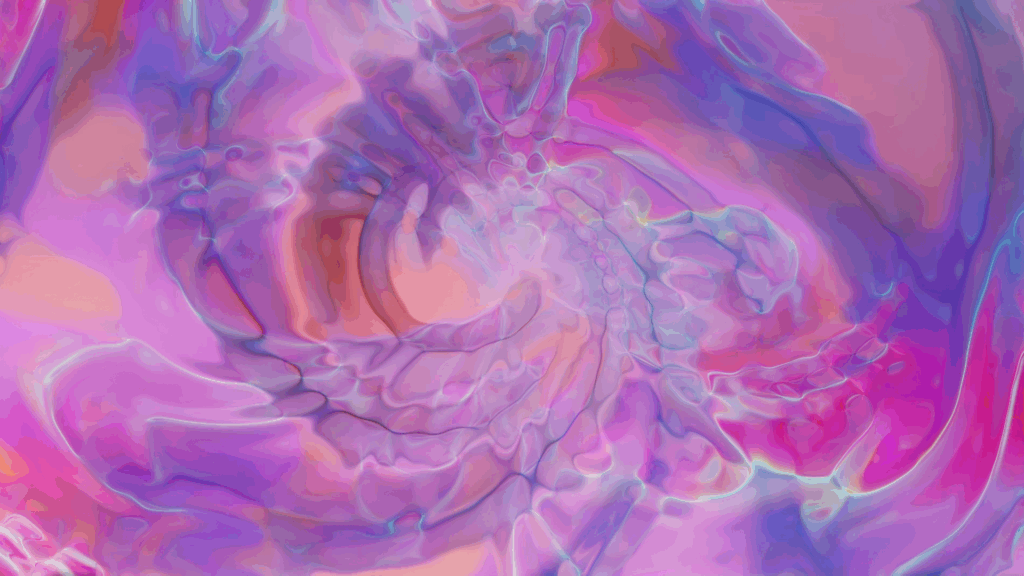

As well as working with other creators, Kinda Studios produce their own pieces which are heavily influenced by their knowledge of the power of immersive on our physiology. One such example is Inspirit, a neuroscience-informed soundscape with beautiful visuals overlayed with a breathwork meditation. The visual and sound dynamics amplify the relaxation impact of the breathwork, and Kinda proved Inspirit’s effectiveness at reducing anxiety through lab testing.

As someone who is far too soft for scare attractions, I have to ask about negative experiences too. Katherine explains that this kind of research is less straightforward: “In psychology we’re not allowed to do scary stuff with people anymore, but in the theatre you are. There was a long time where I felt like I was a black market dealer of negative experiences because I would hook someone creating quite scary experiences up with researchers who are allowed to research them, because we couldn’t create that in the lab ever – ethics would not allow you to”.

Of comparing the placebo effect and immersive theatre, Katherine says “they both show the actual power of mindset, belief, expectation, perception, on the actual physical experiences you’re having. It’s something that you perceive to be real, and anything that you perceive can have this physiological change in effect on your body. I think that’s why immersive experiences can be so transformative and why the placebo effect works, because it is a perception and expectation that then triggers physiological changes in the body”.

Rituals are of particular interest to Katherine, who practises ritual design as part of her work. “There’s lots of elements in ritual designs and my favourite is one called causal obscurity, which is the bit in the ritual that doesn’t make sense. It’s bonkers. It’s like the pineapple on the table. It’s the candles and singing happy birthday. It’s the weird handshake. It’s something that is weird, unknown, unusual, but you don’t know the cause of it, so it’s got an obscure cause. And we know that if you put that in any sort of experience in ritual design it again amplifies it”.

There’s also a ‘priming’ stage, which in this context might include what we refer to as ‘onboarding’, the liminal space between reality and the creative universe you’re about to enter. This might be a holding area where rules are explained, equipment is calibrated, and the mood is adjusted.

As Katherine notes a recent trend in water-based rituals, we touch on the imminent new spa, Submersive, concocted by Meow Wolf co-founder Corvas Brinkerhoff. Submersive promises elevated states of consciousness, with Corvas saying “Our aim is to amass the world’s deepest understanding of how multisensory experiences affect us on a physiological level”.

I’m also reminded of a couple of examples of immersive water rituals I’ve participated in recently. The Liquid Sound festival in Germany added underwater music, responsive visuals and a dusk-til-dawn bathing window to elevate a visit to a thermal saltwater spa, framing it as a night of physical and mental transformation. At PHI Centre in Montreal, Keiken: Sensory Oversoul is a room-scale installation which plays underwater sounds and water-inspired projections around the walls as visitors lay on beds of foam rocks, wearing what I can only describe as an electric womb device which pulses gently – a weird but also deeply relaxing experience.

“We know from ritualistic design that the more ritualistic elements that you have, the more the changes in the body or the greater physical transformation,” explains Katherine. She also points out that awareness of this process actually amplifies it: “If you are told you’re taking part in a ritual, the ritualistic impact on your wellbeing is greater, so again it’s this understanding of it that makes it greater like the placebo effect. There are physiological changes that happen – oxytocin, dopamine, hormones which are produced which have a massive impact on your wellbeing as well.”

Speaking of dopamine, I was also keen to speak to Grant Dudson, Global Creative Director at Fever Originals, who was tasked with refreshing their Dopamine Land experience before it headed to Sao Paulo. Just one of many commercially successful experiences that Fever (and Grant) have created around the world, Dopamine Land sells itself as ‘an interactive sensory museum designed to explore and trigger the happiness hormone dopamine’.

The Dopamine Land design refresh involved visitor feedback on the existing spaces, but also Grant’s own instincts as he decided whether a room was sufficiently dopamine-inducing. “I’ve never been an indie guy,” he says, explaining that part of his creative process is noting his own experience of a space, and assuming he shares the same basic human experience and chemical makeup as his audience, rather than imposing any rarefied artistic sensibility.

“I’m always wanting to make the world a brighter place,” Grant explains. “When I create an experience most of the time, for me, it really comes down to transporting people to spaces and worlds they’ve never been to before, and so I guess when you do that, it does something to you.”

That includes spaces like the Cave of Tactility at Dopamine Land, which is based on heightening visitors’ sense of touch. Grant describes a pool full of sponge cubes covered in soft material, as well as an ASMR soundtrack with 3D audio, and timed lighting patterns.

These carefully considered multi-sensory elements are designed to boost a visitor’s mood as soon as they step through the door, no matter where in the world they are. “The reason we go halfway around the world to the Maldives or Bali or Africa is because we want a shift in the environment we’re in, and that does something to us on a psychological level, for sure. We have the opportunity to bring destinations to our audience.”

Grant also says that his personal fascination with placemaking centres around how art can influence “vibrational change throughout humanity” and that “there’s a level of psychological elevation that immersive experiences or worlds or installations can bring to the everyday environment”. Ultimately, if we feel differently in a place, we can feel differently about a place, and positive changes can follow – it’s the placebo effect at a societal scale.

This leads me neatly to the ultimate case study in immersive environments triggering measurable, physiological changes for the good of society.

Nick Tyler is the creator/director of PEARL, which stands for Person-Environment-Activity Research Laboratory. It’s a 44,000 cubic metre black box space in Dagenham (the footprint of a football field, with a 10m high ceiling) in which the lighting, acoustics and even the smell can be precisely designed to match any real world environment. Within the space, life-sized sets can be built that make it indistinguishable from the real world, turning it into a street, a park, a train platform, or anything else a client needs.

Its purpose, explains Nick, is to influence study participants into behaving exactly as they would in the real world, and to feel the way they would feel under specific circumstances, so that parts of the real world can be redesigned if necessary.

“We can control the world so that we can see how people make those kinds of adjustments, and that means a space in which we can change the lighting and smell and sound and stuff like that. It’s kind of simple, really.”

Simple in theory, but unbelievably complex in technical execution. Modular floor units on actuators can adjust from perfectly flat to 25% gradient, the soundsystem can create an ambisonic dome of audio, and smells can be manufactured and pumped into the air. “The lighting system is the only one in the world that actually matches the colour sensitivity of the human eye,” says Nick. “We had Hollywood in, trying to work out how they could recalibrate their cameras to get better colour, but they needed to know what the human eye can see, and this was the only place in the world that could do that.”

As a result, it’s the perfect place to test how an electric scooter sounds when mixed with the noise of a busy junction, what kind of urban park children with additional sensory needs prefer, or how to ensure a supermarket layout makes sense to people with autism. If this sounds like overkill for feedback on any of the above, there are good reasons PEARL has to go to the lengths they do.

Take, for example, some research on the design of a new tube carriage on the Piccadilly Line, for Transport for London. “They asked us to look at the boarding and alighting processes”, says Nick, “we built one of their trains and we tried different widths of the doors, different heights and gaps between the train and the platform, different arrangements of seating near to the doors inside”.

During the research process, 120 people got on and off the fake train 450 times in three weeks, in an environment designed to look exactly like a tube station. So much effort, but why does it have to be so realistic? Nick explains: “It comes back to the immersiveness of it. If you had tested that in something the exact dimensions of a train, and told people ‘imagine you’re getting on a train’, you can’t guarantee that they would behave as they would if they were actually there. They were in a shed getting off a wooden box, but they had to think they were getting on and off a train. You can see when their interest falls away, and they just get on and off the train, and that’s the data we use.”

Biometric data sits alongside observational data and response surveys from the participants themselves, but the whole picture is needed in order to give accurate feedback, says Nick. “What we’re trying to do is to capture the preconscious ways you’re not aware that you’re responding.

“The kind of model that we are working on is something coming out of theoretical neurobiology, where the brain is a predictive organ and it’s trying to predict how the next moment’s going to be so that it can survive. It says ‘oh, it’s very hot’, so you sweat, but if the brain predicts incorrectly that you’re going to be very hot, you’re still going to sweat. The brain is actually working on the basis of creating illusions. It doesn’t see anything or hear, it just gets electrical signals.”

The various kinds of biofeedback devices Nick and colleagues use to measure people’s responses inside the space include brain scanners, EEG headsets and infrared light devices, gathering data on pupil size, oxygen levels, skin conductivity, and heart rate variability. Despite participants’ knowledge that they’re actually in a lab in Dagenham, these readings reflect that they’re having a completely different experience.

Something both Nick and Katherine touch on separately is rethinking our understanding of the senses, and the impact that can have on our mental state. “We don’t just have five senses,” says Nick, “that’s an Aristotle thing. I’ve got a set of about 70 senses that we use to try and figure out how people are understanding the environment. That ranges from the physiological like vision and temperature, but then you have what I call environmental things like rhythm, dissonance, harmony, contrast, and then the interpretational things like the sense of fairness. Can we make a fair bus stop? Because if it doesn’t feel fair, it doesn’t matter how beautiful it is. That’s also part of our menu, but there aren’t instruments to measure all of those things.”

“Have you heard of interoception?” asks Katherine, “it’s one of the human senses like touch, only it’s an internal one, and it’s the ability to sense the physical sensations in your body that are either to do with bodily processes like hunger, or sickness, or to do with emotions. It’s now known that low interoception is at the base of every mental disorder that has been studied; it’s disconnection from our body, and the emotions that live in our body.”

Katherine theorises that immersive experiences, rather like the ritual involved in the placebo effect, force us to tune into our bodies, and this is where the magic happens.

The power of immersive experiences to affect wellbeing in significant and measurable ways being realised and leveraged by those straddling both worlds. Experts like Sarah Ticho, who is part of the XR Health Alliance. In their report The Growing Value of XR in Healthcare, the XR Health Alliance gives examples of virtual reality headsets combined with biofeedback sensors being used in assessment and treatment of mental health conditions and dementia.

As an artist, Sarah is also the co-creator of VR piece SOUL PAINT, along with Niki Smit. Combining immersive technology, creative storytelling and wellbeing, SOUL PAINT takes audiences on an embodied journey which invites them to tune into feelings – both emotions and sensations – in their bodies. Not just a therapeutic tool, the piece has also won multiple awards at cultural festivals around the world.

Shaking us out of our rhythms altogether, the sense of awe is one that Katherine also highlights as being a particularly powerful tool for transformation. Awe can only be found by taking audiences away from their ordinary worlds altogether, not by replicating them as practitioners at PEARL do, for example. “When you experience awe there’s a very particular neuropattern, a dysregulation of your default mode network. It can be very important to kick the default mode network and of rumination and spiraling thoughts so it can reset.”

“Awe could be huge, epic, with light and sound, or it can be watching an act of kindness, or it can be sitting with a four-year-old as they see a snail for the first time. There’s lots of different types of awe, but it has an incredible ability to disrupt the way you’re thinking and allow for new ways of thinking, which is why for some people, psychedelic experiences are so powerful.”

Working in fulldome, this makes perfect sense. Awe is easy enough to inspire in a dome, because of the sense of scale an artist can create, and I’ve noticed there’s also a lot of psychedelic fulldome content too. One of the most popular fulldome films in this niche is a meditative journey called Mesmerica, ‘designed to relax, soothe, and stimulate your mind and senses’. The producers, WORLDS, are on a mission to use the dome format to have a purposeful positive psychological impact on their audience, with this and subsequent films.

As the domains of wellbeing and immersive continue to merge, I wonder whether we’re at risk of outsourcing our happiness to experience designers, worlds that don’t exist, and clever creative technology.

But an encouraging thread running through each of the experiences I looked at, and each of the conversations I had, was the assumption that we’re leaning into collective experiences which ultimately connect us with other people, in real life. Not only that, but immersive practitioners are increasingly supporting us to access dormant parts of ourselves.

With the continued input of people like Kinda Studios, PEARL, the XR Health Alliance and every creative working in immersive experiences right now, we’re rapidly gaining tools and knowledge that can serve us in the real world, thanks to these masterful illusions.